In the hallowed halls of Oxford’s Merlin College, the most talented—and highest born—sons of the Kingdom of Britain are taught the intricacies of magickal theory. But what dazzles can also destroy, as Gray Marshall is about to discover…

In the hallowed halls of Oxford’s Merlin College, the most talented—and highest born—sons of the Kingdom of Britain are taught the intricacies of magickal theory. But what dazzles can also destroy, as Gray Marshall is about to discover…Gray’s deep talent for magick has won him a place at Merlin College. But when he accompanies four fellow students on a mysterious midnight errand that ends in disaster and death, he is sent away in disgrace—and without a trace of his power. He must spend the summer under the watchful eye of his domineering professor, Appius Callender, working in the gardens of Callender’s country estate and hoping to recover his abilities. And it is there, toiling away on a summer afternoon, that he meets the professor’s daughter.

Even though she has no talent of her own, Sophie Callender longs to be educated in the lore of magick. Her father has kept her isolated at the estate and forbidden her interest; everyone knows that teaching arcane magickal theory to women is the height of impropriety. But against her father’s wishes, Sophie has studied his ancient volumes on the subject. And in the tall, stammering, yet oddly charming Gray, she finally finds someone who encourages her interest and awakens new ideas and feelings.

Sophie and Gray’s meeting touches off a series of events that begins to unravel secrets about each of them. And after the king’s closest advisor pays the professor a closed-door visit, they begin to wonder if what Gray witnessed in Oxford might be even more sinister than it seemed. They are determined to find out, no matter the cost…

Finished

About the Author

Sylvia Izzo Hunter is the author of The Midnight Queen. She was born in Calgary, Alberta, but now lives in Toronto with her husband and daughter and their slightly out-of-control collections of books, comics, and DVDs. When not writing, she works in scholarly journal publishing, sings in two choirs, reads as much as possible, knits hats, and engages in experimental baking. Her favorite Doctor is Tom Baker, her favorite pasta shape is rotini, and her favorite Beethoven symphony is the Seventh.

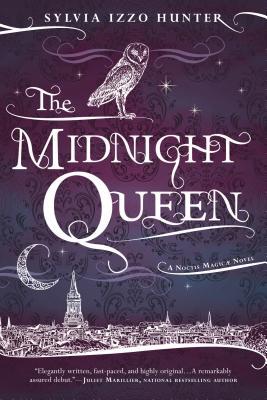

My Review 5 Queenly Stars

If you are looking for an easy, well balanced, fantasy/historical read. Then this is deff the one for you. With a breath taking cover and a great slow to start romance this one will have you reading until the owls hoot. I have to say that Sylvia blew me away with this debut novel and I will deff. Each element in this story grows and becomes important as the story progresses. It was a great read.

Go Into This One Knowing

"All opinions are 100% honest and my own."

Buy The Book

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

***This excerpt is from an advance uncorrected proof***

Copyright © 2014 Sylvia Izzo Hunter

Copyright © 2014 Sylvia Izzo Hunter

Prologue

It was his own fault entirely, Gray reflected later. That morning in Merlin’s South Quad, when Taylor and Woodville had pressed him to join them in some not-quite-specified excursion, he ought to have known that no good would come of it; what good had ever come of Taylor and Woodville before?

“It is a special commission of Professor Callender in the town,” said Taylor. “I am sure he would be very pleased . . .”

“It would do you no harm, Marshall, to render him a service,” said Woodville. “And,” he added delicately, “there may be some coin in it for you, if we speed well.”

A hit below the belt, indeed, but that was only what one expected of Alfric Woodville.

“I have run afoul of the P-proctors b-before,” Gray pointed out. “I am not very eager to do so again.”

“Nonsense!” said Taylor bracingly. He clapped Gray on the shoulder, with some force; Gray stumbled, half in reaction to the blow, half startled by Taylor’s sudden camaraderie. “What can the Proctors do, when we are commissioned by a Senior Fellow?”

Gray had wished very much to know why, if this was indeed his tutor’s business, the Professor could not simply discharge it himself, but he had not been able to get the words out. Having now some inkling of the circumstances, he doubted that Taylor or Woodville would have told him in any case.

“Give me t-t-time to think,” he had said instead.

In the end, however, he had agreed to be of the party. Crowther and Evans-Hughes—good, solid, trustworthy men, though perhaps rather easily led, and the latter in particular always rather short of coin, since (like Gray) he spent too much of his scholarship income in the bookshops of the High-street—had been talked round by Taylor, or perhaps Woodville. They in turn had recruited Gautier, who always seemed to Gray to be in need of looking after, and these three earnestly represented to Gray the advantages to all of having with them the most powerful mage of the Middle Common Room.

After a year’s almost constant disparagement by Professor Callender, Gray dismissed this as patent flattery, but the participation of Evans-Hughes and Crowther did lend a more respectable air to the proceedings.

Finally young Gautier had said, with perfect gravity, “Please, Marshall, do come with us; we should all feel safer, you know.” And Gray—perhaps feeling the effect of having grown up with three younger siblings—had let himself be persuaded.

Thus it was that, in the depths of a murky June night, six Merlin men came to be stealing along Oxford’s New Road in the general direction of their College. The street being otherwise dark and still, their black gowns and subfusc formed a dense creeping shadow against the night.

Taylor and Woodville were cautiously triumphant; the others, knowing themselves by now to be embroiled in something at best equivocal, had long ceased to enjoy themselves and thought only of returning to the safe haven of the College walls.

“What’s the hour?” whispered Crowther.

Evans-Hughes replied, “Nearly one past midnight.”

“Apollo, Pan, and Hecate!” said Gautier. “We shall all be killed on sight!”

“Shut it, you fools,” hissed Woodville.

They were about to round a corner when from over the road came the sound of heavy footsteps.

A moment later a crowd of townsmen was upon them, in drink and in vicious mood. The historic tendency to mistrust University mages, who shut themselves up in book-rooms instead of putting their talents to good honest work in field or pasture or sick-room, was suddenly of very much more than academic import to the Merlin men.

“Look at ’em, sneaking about the streets when decent folk are abed!”

“Aye, and working nasty magicks, I’ll wager.”

The angry mutters crescendoed into shouts: “Have at ’em, mates! Knock ’em down!”

Though few of the townsmen were armed, and none heavily, their advantages in size, strength, and numbers were quickly felt. The air was chill and heavy with dew, and Gray succeeded in drawing down a fall of hailstones, then another and another, which drove back several of their attackers but, alas, only enraged the rest. One flung something at his head; he tried to dodge it but succeeded only in changing the angle of impact. To his left, Woodville had summoned a deadfall tree-limb from someone’s garden and was wielding it, inexpertly, as a sort of flail; to his right, Evans-Hughes bloodied the nose of a young man nearly twice as wide as himself, grinned in fleeting triumph, and then was borne back against Crowther by an answering blow to his temple and fell insensible upon the cobbles.

Taylor, alone of the students, did not fight at all; he was entirely occupied with the teakwood box cradled in his arms, hunching and twisting his body to shield it both from sight and from harm. When the tide of the fight pushed Gray near him, all the hairs stood up on the back of his neck.

Young Gautier darted between two staggering townsmen, caught Gray’s arm, and pressed a handkerchief to his bloodied mouth. “Go and get help, if you can,” he urged, his voice low and urgent. “Get the Professor—get anyone—even if it must be Proctors.”

A moment later, Gray’s gown fluttered down to rest atop a heap of now-outsized garments, and Gautier tossed a large grey owl into the air, to take desperate flight in the direction of the College.

A few lights still burned in upper windows at Merlin, among them that of Appius Callender, Regius Professor of Magickal Theory—tonight playing the expansive host to a party of distinguished and influential guests. The Professor was calling fire to light his pipe when something outside the window caught his eye, and the fire streaked past the pipe-bowl to set his robe alight. Distracted by this embarrassing contretemps, he did not recognise the owl.

The great bird approached the open window and—instead of sailing neatly through it—crashed headfirst into the barrier of a reinforced double ward, fell two storeys, and landed in a heap on the cobblestones.

There it struggled briefly to right itself, then quivered and shimmered and grew into Gray Marshall, sprawling dazed and naked in the street.

Gray staggered to his feet and looked up at the window. “Professor!” he shouted. “Professor, trouble! Help!”

There was no answer from above.

With an effort, Gray raised his voice to maximum volume and bellowed, “Help! Help, anyone! Proctor! Porter! A fight in the New Road—Merlin men in danger!”

Heads began to emerge from windows; Gray turned with profound relief towards the usually menacing sound of the Proctors’ men erupting from the Porter’s Lodge near Merlin’s back gate. “The New Road,” he repeated.

Then he swayed on his feet, reached out for support, and, failing to find it, collapsed, striking his head hard upon the cobbles.

Gray woke, groggy and with pounding head, in utterly strange surroundings—not in the Infirmary, nor in his own rooms overlooking the Garden Quad, but (he eventually discovered) lying on a pallet in what seemed a windowless box-room, and covered only by a rough blanket, long unlaundered.

His head ached so that he could scarcely think. His first efforts to sit up and look about him proving spectacularly unsuccessful, he subsided, retching and gasping for breath, to his original supine posture.

Eyes closed, he lay still, sorting out the half-familiar smells. Pipe tobacco was among them, he decided at last; bergamot, juniper, mace; a nose-wrinkling undertone of asafoetida.

“Mother Goddess!” Gray whispered suddenly. The smell was very like his tutor’s study.

The room was dark; no door was visible. Stretching out his hand, he tried to call light—as he had done thousands of times since first learning to use his magick as a child—the better to investigate his surroundings.

It was when the effort failed, and left him dizzy and seeing spots, that he began to see what trouble he was in.

Approaching footsteps warned Gray an instant before the door opened. Instinctively he closed his eyes and relaxed his limbs, breathing deeply to feign sleep.

“Well?” A bass voice, impatient.

“There; do you see?” he heard the Professor say. “The boy fancies himself a master shape-shifter and has drained his magick down with that idiotic stunt. He will sleep for hours yet.”

More footsteps.

“Very well,” said the basso. “He will give thanks for a lucky escape, I should hope.”

“And you are certain the wards on the outer walls will hold?” said another voice—this one higher and faintly nasal.

“What do you take us for?”

“Leave the boy, then; we have not finished.”

The door closed, the footsteps retreated; but Gray, now listening hard, could still—just barely—hear the voices, though their words came to him only in disjointed phrases.

“We dare not act before the Samhain term,” said the nasal voice. “. . . too much groundwork left to lay . . . afterward we shall have little time to prepare . . .”

“. . . great pity that your students failed you so badly, Professor,” said the basso; his tone rode the knife’s edge between commiseration and mockery. “I know . . . counting on them to provide—”

“We do not know yet that they have failed,” the Professor retorted, louder. “All we do know is that they were waylaid on their return. I shall see tomorrow how they have sped.”

“And can another such attempt be made . . . seek it elsewhere?” This was the nasal voice, which Gray was finding more and more unnerving.

“Leave all of it to me.” The Professor’s tone grew louder yet, impatient. “What would you have me do? If your involvement is revealed, then all our efforts here will have been for naught. You must let me work in my own way.”

“But of course,” his companion replied, soothing now. “You must . . . think best.” Then his voice sharpened, and Gray heard him clearly: “Only make very certain that no one can draw any connexion to you, or to any of this night’s doings, when the Master is gone. Do not give me cause to regret granting you the choice of subjects to test your method.”

At this Gray, who had been sitting upright, one ear pressed to the box-room door, fell back with a little gasp. I am dreaming, surely. Have I just now overheard a plot to do away with the Master of Merlin? No—surely this is only some academic contretemps? Mother Goddess, bountiful and kind, wake me from this nightmare . . .

“Marshall!”

Gray woke again, slowly and painfully, to the Professor’s impatient voice. Sleep had not helped him; on the contrary, the blinding headache and general malaise had been joined by a wide assortment of very specific aches and pains.

Worst, he was still stark naked in his tutor’s box-room—and desperately needing the privy.

“I am awake now, sir,” he managed to say. June sunlight streamed in the open doorway; he screwed his eyes shut against the pain. “S-sir, are—the others, are they—”

“Nothing you need worry about, my boy,” the Professor replied, with the heartiness Gray had come to dread. “Taylor and Evans-Hughes are in the Infirmary, but the healers tell me they will be themselves again in no time at all.”

He did not address the obvious questions: What of the rest? Why was Gray here, and not in the Infirmary with Evans-Hughes and Taylor? How long had he been here?

A scout loomed behind him in the doorway, carrying a stack of folded clothes, a basin and ewer, a towel, Gray’s shaving kit. He looked about him impassively for some surface on which to place them.

“Now, Marshall,” the Professor went on, “I have sent for some things from your rooms, and when you have washed and dressed I shall take you to the Infirmary. Though there is very little the matter with you, I expect.”

Gray was about to blurt out that something was very wrong indeed, but it had become a matter of instinct with him by now never to offer his tutor any unnecessary advantage over him. “Y-y-yes, sir,” he said instead.

“Good, good. On you go, then.” And the Professor was gone, leaving Gray alone with the scout.

“You may as well put all of it on the floor,” Gray said, wearily. “What can it matter? Here—let me take that.” He relieved the man of the basin and ewer. “And I thank you. I am much obliged to you.”

“Sir.” The scout, looking faintly surprised, nodded at him, then began dusting off a trunk to serve as a dressing-table.

Gray set down the basin and ewer and looked through the pile of clothes. There was a handkerchief that was not his—a minuscule AG was embroidered in one corner—and something else vital was missing. “Do you—” He stopped. “I b-beg pardon; I do not know your name . . .”

“Baker, sir,” said the scout, without looking up.

“Baker, I wonder—do you know what became of my gown?”

“I am sorry, sir,” Baker replied. “I couldn’t rightly say.”

Once in the Infirmary, Gray contrived to escape, briefly, from the Professor and the chief healer, and found Taylor and Evans-Hughes in adjacent beds, both looking battered and miserable. This was not unexpected—very probably he looked the same himself—but he was shocked by their reaction to his arrival.

Taylor, whose fault all of this was, if anyone’s, narrowed his eyes and turned his bandaged head away; gentle, bookish Evans-Hughes greeted him with curses.

“What—” Gray began, then stopped, bewildered.

“How dare you!” Evans-Hughes growled. “How dare you show your face, after—”

“Don’t talk to him,” said Taylor.

“What is it you suppose me to have done?” Gray demanded. “What happened, after Gautier sent me for help—”

“Sent you for help!” Taylor scoffed, ignoring his own advice. “How easy to make such a claim, now he cannot speak against you.”

“Cannot—why not? And where is he?”

The other two exchanged a look that Gray could not interpret.

“The Proctors brought him in,” said Evans-Hughes.

“Dead,” said Taylor.

Gray’s stomach lurched, and he sat down, hard—on the floor, there being nothing else within reach. He felt the blood drain from his face. Only last Beltane-time they had all drunk to Arzhur Gautier on his eighteenth birthday . . .

“But the Professor . . . the P-professor said . . .”

Before he could finish his sentence, two strapping healer-assistants, dispatched by their master, came to haul him up by the arms and march him away to a hot bath, and thence to bed.

The Professor was waiting for him there, wearing his heartiest and most insincere smile. “Marshall,” he said at once, “I have decided that you shall accompany me to my country home, and remain there for the Long Vacation. It will do you good to spend time in different surroundings. And, of course, I should otherwise be forced to agree with Proctor Morris that your actions in abandoning young Gautier to his fate cast into grave doubt whether you merit a place at Merlin—much less the continuance of your fellowship. You will much prefer to consider your situation at some distance, I am sure.”

It was a command and a warning—not an invitation—and there was only one possible response. “I thank you, sir,” Gray said miserably.

All along their journey—to Portsmouth and across the Manche to the province of Petite-Bretagne, at the eastern edge of the kingdom—Professor Callender kept Gray closely leashed. At one posting-inn, some way inland from the port of Aleth, Gray contrived a few unwatched moments in the taproom, where a silver coin he could ill afford to part with secured him a bottle of ink and a sheet of rough note-paper, and wrote a brief and anxious note to Henry Crowther. The barmaid accepted it from him, and promised to see it safely into the next post-bag bound for England; on running him to earth, however, the Professor scolded him so caustically and publicly for leaving his rooms that Gray fully expected her to think him a lunatic and drop it into the midden-heap instead, and could not summon the necessary resolve to try again at their next halt.

In every idle moment, his mind reverted to that half-overheard conversation in the Professor’s rooms. Unquestionably there was a conspiracy of some kind, and the Professor deeply involved in it. Who had those two men been, whose voices now seemed burnt into his mind’s ear? That they meant ill to Lord Halifax, Master of Merlin College, was plain. But ill of what sort? What did they hope to gain by his removal, and how did they mean to achieve it?

Had Woodville known of this? Had Taylor? What of the others? Not Evans-Hughes, surely. Not Crowther. Mother Goddess, not Gautier!

What did the Professor believe Gray to have done, or heard, or seen, that they had not, that he should keep Gray—alone of the more than half-dozen men conscripted to that ill-starred errand—so close at hand?

And, supposing that he attempted to tell someone the little he had overheard—if it had not been only the product of magick-shocked delirium—who would believe him?

If there was a way out of this tangle, Gray could not see it, try as he might. I know what I am running from. What am I running towards?

0 comments:

Post a Comment

Hateful and Unrelated Comments Will Be Deleted. Anonymous comments are invalid to enter into giveaways.